SELinux/Type enforcement

Type enforcement is the notion that, in a mandatory access control system, access is governed through clearance based on a subject-access-object set of rules.

Introduction

Access control has always played a role in computing systems, and even before that. Many people understand a negative access control model ("You are not allowed to go inside that room") because it is what they, as subjects, learn when trying to do something not allowed by the access controls (i.e. trying to go inside a room). However, the positive rules (what they are allowed to do) are well known, explicitly or intuitively.

In a subject-access-object rule set, enforcement is documented line by line. Each rule stands by itself; if something is explicitly allowed in a rule, then it is allowed (regardless of other rules). If something is not explicitly allowed, then it is denied (deny by default).

Such rules can be read as "Subject foo is allowed to do access on object."

Subjects

In security parlance, subjects are actively performing an action. On a Linux system, subjects are processes (as it is a process that is executing the code of an application) and, through processes, users (as every action taken by a user is something interpreted and handled by a process, be it the user shell or the graphical environment).

In security architecturing, subjects are also often mentioned as actors.

Access

An access is what is allowed (or denied). An access is an activity, such as "entering" (in our example of entering a room) or "reading" (on files). It is also often documented as a permission.

By itself, an access doesn't mean much. The action/permissions "read", "open", "append", etc. mean nothing without subjects and objects. Instead, the set of supported actions in a type enforcement access control shows the granularity and ability of the access control.

Object

The object is the resource on which an action applies. Objects do not actively perform anything - type enforcement is a one-way definition. A process might be allowed to signal an other process - or it might not. There is no "signal another process if that other process is reading a file" or "kill a process that is writing a core file".

Type enforcement in SELinux

In SELinux, type enforcement is implemented based on the labels of the subjects and objects. SELinux by itself does not have rules that say "/bin/bash can execute /bin/ls". Instead, it has rules similar to "Processes with the label user_t can execute regular files labeled bin_t."

Domains

In SELinux, the label assigned to a process is also called a domain. In fact, most documentation will talk about SELinux domains when it is meant to be the security context of a running process.

An example of a SELinux domain is system_u:system_r:named_t, although that is often reduced to just the type-part, i.e. named_t.

root #ps -ef | grep namedsystem_u:system_r:named_t named 30061 1 0 22:05 ? 00:00:00 named

The fact that SELinux uses labels means that it does not care which process is running with that label. The label itself is what SELinux works with. Access decisions are purely taken based on the label. Other aspects of the subject (process) do not play any role.

Types

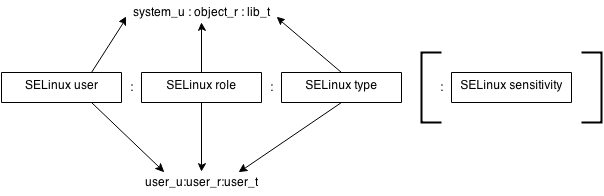

The term type is used for a label assigned to an object, although sometimes the term is also used for the label of a process, i.e. a domain. This is because in a SELinux context, the third field is called the SELinux type.

Like with SELinux domains, SELinux is only interested in the label of the resource with one exception: its class.

The class of the resource also plays a role in the decision making of access controls. For SELinux, there is a huge difference between the following rules:

allow user_t bin_t:file read;

allow user_t bin_t:lnk_file read;

allow user_t bin_t:dir read;

As a result, the object for SELinux is the combination of the label with the class.

Attributes

SELinux has a particular feature that allows grouping access control rules, called attributes.

A domain or type can be assigned an attribute, and access control rules can be defined on attributes (both on subject level, object level or both). When checking the access of a particular subject, its label is checked for supported attributes and rules on that attribute are accepted as well. Similarly, the label of the object is checked for attributes and rules on that attribute are also used.

This allows a single rule to be used to say that "Every user domain can execute files labeled as bin_t":

allow userdomain bin_t:file execute;

Through attributes, this rule is valid for all types that are assigned the userdomain attribute:

root #seinfo -auserdomain -x userdomain

logadm_t

sysadm_t

webadm_t

unconfined_t

...

Permissions

The supported accesses performed by the subjects towards the objects are the permissions that SELinux supports.

For each resource class (the class of the object) SELinux has a set of permissions that it supports. The supported permissions can be viewed through the selinuxfs file system. For instance, the supported permissions for the regular file class:

user $ls /sys/fs/selinux/class/file/permsappend execmod getattr lock quotaon relabelto swapon create execute ioctl mounton read rename unlink entrypoint execute_no_trans link open relabelfrom setattr write

If an access is not mentioned in the list of supported permissions, then either it isn't handled by the Linux kernel (as the accesses are all kernel-verified activities) or it isn't known to SELinux yet. In the latter case, the policy can be configured to either allow unknown permissions or deny it. On Gentoo, the default is to deny it.